First Pages: Twilight Men by Andre Tellier

Welcome to First Pages on Fridays! Every Friday, we share the first pages from a book (usually vintage), along with a bit of information about the author and the book’s history.

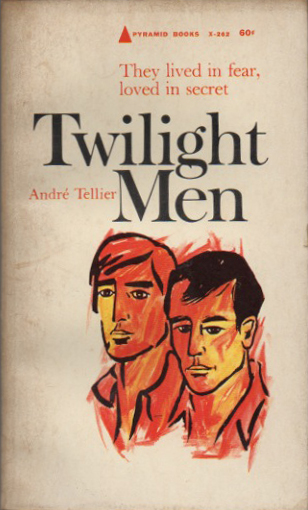

This week’s selection is the gay pulp novel Twilight Men by Andre Tellier. This novel was first published in 1931 and received some attention, going through several printings over the next couple of years. The paperback edition pictured above was published in 1957 by Pyramid Books (New York).

Like many early gay novels, the book does not have a happy ending: the main character becomes addicted to drugs, murders his father, and kills himself. This theme (the gay monster or the gay degenerate) occurs very frequently before the 1960’s. Originally, this was the only way that a book with any kind of gay themes could even be published; that is, it was only palatable–or even legal–to feature a gay protagonist if that person “gets what’s coming to him” in the end.

The February 1934 issue of Chanticleer, a gay literary “magazine,” includes reviews by Henry Gerber of several novels, including Twilight Men. He wrote: “TWILIGHT MEN, by Andre Tellier, deals with a young Frenchman, who comes to America, is introduced into homosexual society in New York, becomes a drug addict for no obvious reason, finally kills his father and commits suicide. It is again excellent anti-homosexual propaganda, although the plot is too silly to convince anyone who has known homosexual people at all.”

Little has been written about the author, Andre Tellier, himself. He wrote other books, including A Woman of Paris, The Magnificent Sin, Vagabond April, and Witchfire; but nothing else is really known about him.

Enjoy this excerpt from Twilight Men!

Chapter 1

“Monsier Josef Bironge–”

Comte de Rasbon had not turned from the desk before M. Bironge’s stocky, robust figure waddled briskly into the room, clad in its usual neat, black business suit. A mahogany cane swung smartly from his left elbow, the ends of a red silk bandanna drooped like a signal of distress from his right hand. The wrinkles on his high, bald forehead were aggravated by a worried expression that pushed his eyebrows upward.

“You received my letter, Edmond?” Bironge approached the desk and drew a chair near the Comte’s.

“Yes, Josef, last night. Have you brought him?”

“On his eighteenth birthday, as we agreed.”

“How the time flies! Is it already the second of June?”

“It is.”

Planting his cane upright between his spread legs, his hands clasped on the top of it, Bironge sighed plaintively.

“Naturally he’s much changed from the youngster you called ‘spidery’ at my house six years ago. I’ve thought several times of writing you, but your address was so uncertain and I didn’t want to disturb you.”

“But you have disturbed me. Last night’s letter disturbed me very much.” His fist came down on the desk. “Josef, how does this thing happen? I feel so strongly about the matter I’d rather know he was dead!”

“You don’t mean that, Edmond.”

“I do. Why didn’t you put him quietly out of the way? What is death–nothing! But this–a young man of his sort never amounts to anything.”

Bironge shifted uneasily. “I tried my best–”

“Your best!”

“He has excellent points, Edmond.”

The Comte made a disgustful gesture. “It’s my rotten luck to have a son like him! For eighteen years I’ve wasted time in plans, thinking he would take after me.” He drew himself erect. “What a humiliation to have this weakling bear my name! I can’t have it. Josef, I can’t, I tell you. Good God! To have people pointing at him and saying, ‘That is the son of the Comte de Rasbon!’ Wildness I could have excused, that at least would have been strength. But this! He might as well be a cripple–”

Bironge cleared his throat nervously. He was being put in a very unpleasant position.

“I hold a detached view towards matters of sex,” he said with an air of superiority he did not feel. “Armand is a youth of fire. There’s no reason to speak of him as crippled.”

“Oh, well! Let’s get this disagreeable meeting over at once.” The Comte rose. “Where is he?”

“Waiting in my car, and he detests waiting. You may change your opinion when you see him. He’s a handsome lad, splendid qualities. After all, Edmond, he is not to blame. We all have our idiosyncrasies.”

Another disgusted gesture from the Comte. Bironge grew irritated.

“If you don’t care to acknowledge him, don’t. He’s not legally your son. Hand him over to me, let him continue to bear my name, and tell him nothing. But it’s a rotten way to treat Antoinette’s son.”

“If he weren’t her son I’d not see him at all. Do you think I feel nothing?”

“I know, I know.”

A drop in his tone told the Comte he was being pitied. He bristled. “You know? How should you? How should anyone know what’s been going on inside of me since she went? How often we talked it over. Our son. He was to take up my interests, do all the big things I had dreamed of, and then death snuffed her out. It’s always like that. I never dreamed a dream but fate balked me. Life has treated me very badly. It has never given me the happiness it promised. She died too soon. Now he disappoints me.”

“But he’s not dull. He’ll make a name for himself by and by.”

“A name! A name as an ass!” He clenched his hand fiercely. “Why don’t you throw him among women and let them make a man of him!”

“But he says they’re silly. He prefers to scribble in his room.”

“No de Rasbon ever turned his eyes from a woman except to look at another. Well, mention something, anything, that shows he has my blood in his veins.”

Josef shook his head. “Only his temper. For the rest, he’s more like her. He loves soft things, dreams over Christina Rossetti, scatters caresses to horses. I’ve even caught him kissing a honeysuckle that grows over my terrace. But what of that, Edmond–poets are like that, aren’t they?” He livened. “Mark my word, one day he’ll astonish us.”

“No doubt.”

“Edmond, listen. His case isn’t so rare. Every now and then a child like that is born, generally of a wild father.”

“I’m to blame now, am I?”

“Certainly not, but let me tell you there’s never been a criminal, a harlot, a pygmy or a giant yet whose case couldn’t be traced back to wild oats sown by some ancestor. Black oats, scarlet oats, whatever it was that springs to harvest in the last poor devil. Who knows but what those too good times of yours–”

“I understand, ‘the Sins of the Fathers.’ How convenient! Well, you needn’t think I’m going to shoulder the responsibility. I gave him over to you, with carte blanche to bring him up as you please, provided he grew up a gentleman. You should have anticipated this and remedied it as soon as the symptoms appeared. I’ve made up my mind–I won’t see him–”

But the door was already being pushed open cautiously. A slender young man of medium height stood in the doorway, hat in hand. He was dressed in a white suit that only emphasized his youth. He had gold-brown eyes, and over his right eyebrow a blond curl drooped conspicuously.

The newcomer looked with interest at the tall, haggard man who was pacing the room excitedly. He noticed, with his peculiar trick of immediately observing details, that the man’s lips were full and red, without the usual purplish look that comes with age.

“Good Lord! I nearly died of waiting–”

He hesitated on the threshold, ill at ease and self-conscious, as though uncertain whether or not he would be allowed to interrupt this conference. Then, resorting like a child to a gesture which had always been effective, he tilted his head to one side wistfully and asked, “Won’t somebody please say ‘come in’?”

De Rasbon had stopped pacing the room. He was half-conscious of a sudden vertigo that prevented him from speaking. He observed the boy eagerly and reluctantly, noting the large, almond-shaped eyes of the de Rasbons, and the complementary golden hair and petulant mouth of the dead Antoinette.

A slim, long-fingered hand was offered to him nervously. For a moment the Comte hesitated. There was a certain appeal about the boy, but because that appeal was so fragile, so nearly dainty, so dangerously near the feminine, it only resulted in repelling him.

Josef was already introducing with a negligent wave of the hand. “My nephew, Armand–” his hand swept in the other direction, “Comte de Rasbon, friend of my childhood–”

The Comte touched the proffered fingers almost distastefully. Josef, ill at ease because of the awkward pause which ensued, edged towards the door, speaking according to a prepared schedule. “A little errand, Edmond. I’ll be back later.”

Father and son were left staring at one another, the father with an air of embarrassment, the son with friendly curiosity.

With the gesture of an accomplished poseur, the boy tossed the curl back from his forehead. Armand’s lips trembled slightly, as though groping for some small remark which would relieve the strain of silence. For a reason which he could not understand, he himself was beginning to feel embarrassed too.

“I’ve heard of your reputation as a financier, Comte de Rasbon,” he brought out at last in a high, nervous tone which harassed the Comte. He did not answer. He merely stared, and when at least he did speak, his words carried a note of sarcasm.

“I asked your uncle to bring you here because I am interested in you.”

“Really?” The boy was suddenly eager, as though he were anxious to be liked and approved of, but had had little expectation of it.

“Yes,” said de Rasbon thoughtfully. Then, with a motion toward the desk littered with papers, he asked tentatively.”How would you like to become a man of the world, a businessman?”

Armand approached the desk, sank into the chair beside it, rested his elbows on the wood, and brought his tapering fingers together. His smile was almost penitent.

“Uncle Josef and I are always fighting about that very thing, Comte de Rasbon.”

“So?”

“Yes.” He seemed to be trying to couch what he had to say in the least offensive terms. “You see,” he continued apologetically, “business isn’t my idea of happiness.”

“No? May I ask what is?”

“I like to write–” his voice trailed uncertainly off into silence.

De Rasbon did not answer, but his nostrils quivered slightly, and he made an involuntary motion of impatience. Armand moved nervously.

“I’ve found life largely an affair of two rooms, Comte. The outer room, ridiculously small and narrow–and the inner room of the soul, which is vast.” He delivered this speech with sudden intensity, and then, as though aghast at his own temerity, hid behind a quick silence. With a polished thumbnail, he started to trace the line of carving on the desk-edge.

De Rasbon remained silent, bitter thoughts racing through his head. Interlaced with them were memories, hopes, and a swarm of disappointments. He felt that this boy, who did not even know of their relationship, had somehow betrayed him, and deliberately. When at last he did speak again, his tone was sharply edged.

“To dream! That’s all very well in its place, no doubt. But when a man is young, he has to fight.”

The boy lifted his head quickly. “Oh, I shall never fight,” he answered. “I shall ask nothing of the world, nothing at all, except to be left alone.” Again he tossed back the drooping curl. “Why should I play the snatch-and-keep game?” he asked. “I could never sit for hours at a desk, I’m altogether too restless. I like to be alone and–and think.” Again, that sudden dropping of the voice. “I–I’m sorry, Comte. I must be boring you. Uncle Josef says I talk too much about myself–” He returned to his tracing of the carving as though to cover his confusion.

The Comte cleared his throat. “Oh, not at all,” he said, trying to be reassuring. “Do go on. Tell me about yourself.”

Armand laughed softly. “You’re only being polite, Comte. You’re a businessman.” He laughed again, contritely. “Uncle took me to a business lecture not long ago. I feel asleep.”

“Really?” A touch of derision, in spite of himself.

“Yes. The man was stupid. He said business has a soul. It hasn’t. It’s just warfare between one man and another to see which can get the most money. That doesn’t interest me. There are so many things one would have to give up.” He shrugged. “The price is too great.”

“Then you like to be idle?”

“Oh, no, not at all! The longest week I ever spent was when I lay ill in bed. I hated it.”

De Rasbon observed the almost effeminate gesture with which the boy smoothed back his curls, and the coquettish manner he had of narrowing his eyes as he talked. In an access of fresh self-pity, he took out an immaculate handkerchief and blew his nose.

The boy talked on. “No, no, I don’t like idleness. But I think everyone is entitled to enough leisure to dream out his thoughts and see if they are worth anything.”

“I’m afraid I don’t quite understand.”

“Neither does Uncle. He says I’m foolish, and from his standpoint, I suppose I am. But I know what I want. It comes to me more and more when I’m lying in the grass. Sometimes when I wake up at night I seem to be filled with a great disgust for life, doing little things every day as if rules were what we’re made for. There’s no satisfaction in life as I have to live it, getting up at a certain hour, breakfasting, doing the same things in the same way every day. It it wasn’t for Uncle’s being so opposed to it, I’d travel and see something of the world.”

“You’d like to travel?”

“Yes, I’d like it tremendously.”

The Comte looked into the eyes that met his frankly, and withdrew his gaze distastefully. “Better stay at home,” he advised in the blandest tone. “You might get seasick.”

The boy took it in good faith. “Oh, I would. People with complex emotions always are.”

“Indeed! Perhaps that is their way of getting rid of some of them.” He laughed suddenly. “And your complex emotions–do they include women?”

“I don’t like women, Comte.” He was quite naive.

“Have you had so much experience with them, then?”

“No, hardly any. But they don’t inspire me.”

“Oh! So it’s inspiration you’re after! And may I ask you where you do get your–er–inspiration?”

“From the fields, from the trees–”

“Trees! Good God, what next? From insensate wood?”

“Trees are not insensate, Comte.” He at last realized that he was being ridiculed, and from this realization he seemed to have gained a sort of sullen determination to declare himself. In fact, he seemed to be fighting for something, but his manner was groping and puzzled, as though he himself did not know the object of this struggle. “Trees have consciousness. When they talk, they say things. I am happy when I am sitting under a tree. I am alone with it.” He turned with a gesture of inquiry. “Have you never tried that, Comte?”

“Tried what? Sitting under a tree? I’ve sat under lots of trees, but it’s not so much fun alone. Besides, there are always the ants.” He derived a certain satisfaction from being deliberately obtuse.

“But you don’t understand!” The boy looked hopeless and resigned. The Comte caught at his advantage.

—–

To purchase your own copy of Twilight Men by Andre Tellier, visit Abebooks.com.

To browse other titles like this one, visit the Somewhere Books online store.